Author: Cybersecurity Expert Julie Baker

Electronic voting—using computers to cast, count, and manage votes—sounds futuristic and efficient. But it’s a terrible idea, riddled with flaws that undermine the integrity of elections. From complexity to vulnerability, the risks are overwhelming. Let’s break down why electronic voting, in all its forms, fails to deliver secure and trustworthy elections, and why alternatives like blockchain and mobile voting don’t solve the problem.

The Core Problems with Electronic Voting

Complexity: The Enemy of Security

In cybersecurity, complexity is a death knell for security. The more intricate a system, the harder it is to secure. Modern electronic voting systems are a labyrinth of components—hardware, software, and networks—each a potential attack vector.

Consider this: today’s voting machines rely on millions of lines of code—3 to 4 million, to be precise—just to count votes. That’s absurd. Any developer will tell you that counting votes shouldn’t require such bloated software. Analyzing this much code for vulnerabilities is a Herculean task, taking years. And with every update, the process starts over. It’s almost as if the systems are designed to evade scrutiny, cloaked in unnecessary complexity.

Centralization: Loss of Local Control

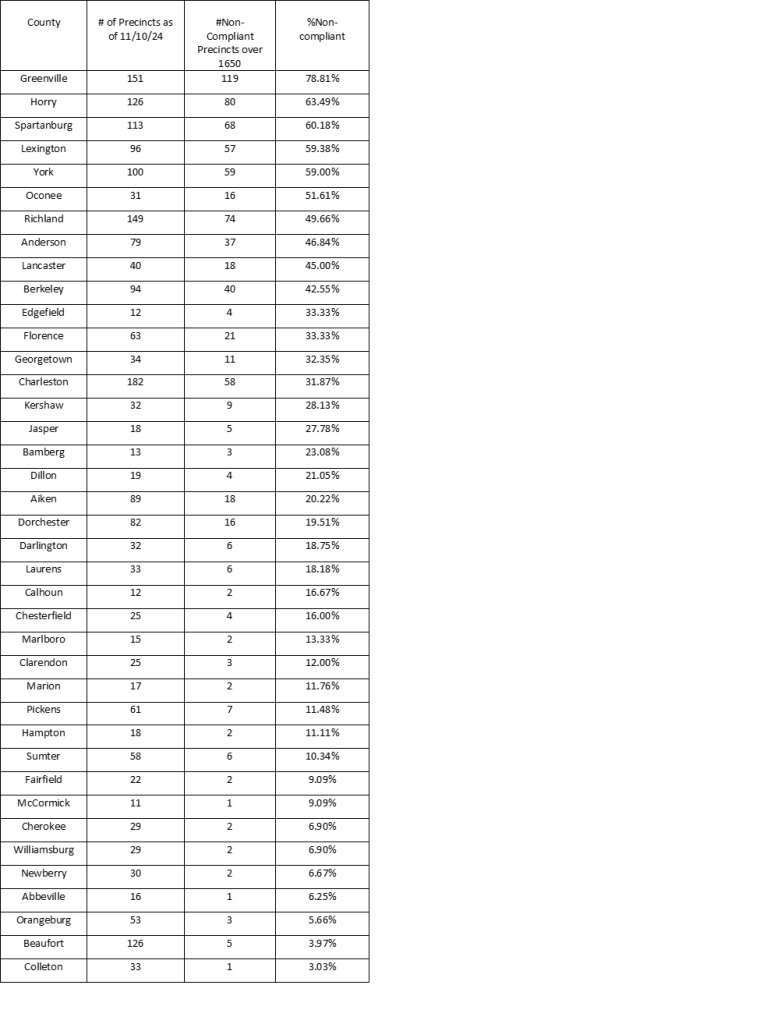

Centralized voting systems strip away local control, handing power to distant entities. Federal involvement in elections—through agencies like CISA, ISACs, the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), and laws like HAVA—introduces risks. Tools like Albert sensors and the Center for Internet Security further erode local oversight. Even at the state level, centralization is a problem. South Carolina, for example, runs a fully centralized voting system from Columbia. When control is concentrated, voters lose their grip on the process. Can centralized control ever be trusted in elections?

Outsourced: Who’s Really in Charge?

Our elections are largely outsourced to private companies like ES&S, Dominion, and Hart InterCivic, many of which are owned by private equity firms. This raises serious questions about transparency. Who are the investors? What’s their security posture? We don’t know, because these companies operate in the shadows, often relying on other third parties—some not even based in the U.S. With so much of the process outsourced, local control is a myth.

Opaque: Black Boxes We Can’t Trust

Electronic voting systems are black boxes. The source code is proprietary, not open-source, so no one outside the companies can inspect it. You can’t pop open the machines to check the hardware either. Is there a cellular modem inside? No way to know. Cast Vote Records (CVRs) and audit logs are often inaccessible, and private companies aren’t subject to FOIA requests. Without transparency or the ability to audit, how can we trust the results?

Vulnerable: A Hacker’s Playground

Software is inherently vulnerable. Developers make mistakes, and those mistakes become exploitable weaknesses. Every update introduces new vulnerabilities. Even air-gapped systems—those supposedly isolated from networks—can be compromised via infected USB drives. No electronic system can ever be 100% secure. Bad actors can manipulate software in real time, leaving no trace. The risks are not theoretical; they’re inevitable.

Can Blockchain Save the Day?

Blockchain—a decentralized, transparent, and immutable digital ledger—sounds like a dream solution for elections. It’s used for cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, as well as real estate and financial transactions. Its appeal for voting is obvious: a secure, tamper-resistant system with no central authority. But is it really the answer?

The Blockchain Mirage

Blockchain isn’t a silver bullet. It’s not just the ledger; it’s the entire ecosystem—software, hardware, third-party integrations, and cryptographic key management—that introduces complexity. And complexity, as we’ve established, breeds insecurity. Blockchain systems can be public, private, or hybrid, permissioned or permissionless, centralized or decentralized. The devil’s in the implementation.

Real-world attacks on blockchain systems prove their vulnerability. Hackers have targeted wallets, cryptographic keys, consensus mechanisms (like 51% attacks), networking protocols (Sybil, Eclipse, DDoS), APIs, decentralized apps, exchanges, smart contracts, and even the foundational blockchain software. Losses have reached billions. Where there’s value—whether money or votes—attackers will follow. Nation-states, too, have a vested interest in controlling or disrupting elections. A truly decentralized, transparent blockchain for voting? Don’t hold your breath—governments like centralized control, as seen in Romania’s 2020 and 2024 elections, which used the EU’s centrally controlled blockchain.

Mobile Voting: A Disaster in the Making

Mobile voting—casting ballots via smartphone—sounds convenient, but it’s a nightmare. A group funded by Tusk Philanthropies is developing a mobile voting system, potentially for use in upcoming midterms. Here’s why it’s a terrible idea:

- Partisan Roots: Despite claims of non-partisanship, the developers lean left, raising concerns about bias.

- No Security Gains: The system aims to be “as secure” as current voting systems—which, as we’ve seen, are far from secure.

- Shady Ties: The cryptography has links to the NSA, DARPA, and Microsoft, and foreign third parties, like a Danish company, are involved in development.

- Complexity Overload: It’s as complex as, if not more than, existing systems, with all the same vulnerabilities.

- Weak Authentication: Relying on SMS or facial recognition opens the door to fraud via synthetic identities and cell phone farms.

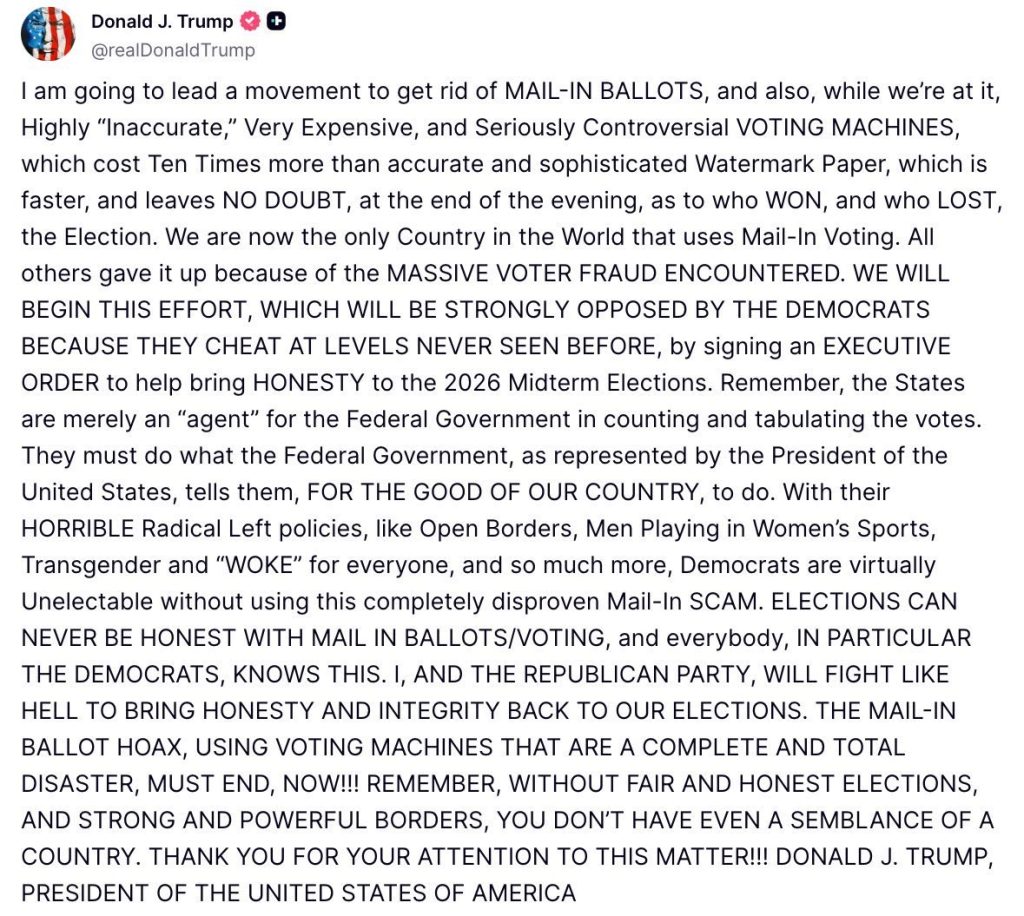

- Mail-in Voting 2.0: The system is pitched as a replacement for mail-in voting, which President Trump has criticized. It’s essentially mail-in voting on steroids, amplifying the risks of fraud.

The claim that voters can track their ballots “all the way through” falls apart when ballots are transferred to an “air-gapped” system for printing and tallying, breaking the chain of transparency.

The Bottom Line: Electronic Voting is Irredeemable

Whether it’s current systems, blockchain, or mobile voting, electronic voting is plagued by the same issues:

- Complexity: All these systems are overly complex, creating countless attack surfaces.

- Centralization: Implementation matters, but nation-states and private entities prefer control over transparency.

- Opacity: Lack of access to code, hardware, or audit logs undermines trust.

- Vulnerability: Software and hardware are inherently flawed, and attackers exploit those flaws.

- Outsourcing: Private companies, often with opaque ownership, control the process, eroding local oversight.

With the rise of AI and quantum computing, these vulnerabilities will only grow. Banks set aside millions for fraud and buy cyber insurance because breaches are inevitable. But elections aren’t like banks—you can’t tolerate any fraud. You get one shot, and the system must be 100% secure. That’s impossible with electronic voting.

The Solution: Back to Basics

Electronic voting, in all its forms, enables cheating at scale. Blockchain and mobile voting are shiny distractions, but they’re just as flawed as current systems. The only way to ensure secure, transparent, and trustworthy elections is to return to paper. Hand-marked, hand-counted paper ballots are simple, auditable, and resistant to large-scale fraud.

Say no to blockchain voting. Say no to mobile voting. Say yes to paper. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the only way to protect our elections.